I was brainstorming writing topics with the family, when I told them I wanted to do a “Top 5” list of television detectives, a genre that I love. The questions and debating began immediately. “Well, how far are you going to go back?” asked Greg who has recently become fan of Jack Webb and Dragnet, watching that 1950’s show on Netflix. Pretty soon we were all immersed in a challenge just to pick out the top 5 Dick Wolf characters from the Law and Order franchise. Just for background, I skimmed a few “Top TV Detective” lists that I Googled and discovered passionate devotion to shows and characters that I had never even heard of.

So, my blog, my rules. I decided to stick with shows that are reasonably current and with which I am familiar. I decided that there would be no attempt at gender balance, so my apologies to SVU’s Olivia Benson, The Killing’s Sarah Linden, and Prime Suspect’s Jane Timoney, all tough, wonderful characters.

That does not mean that I did not establish some criteria. All of my chosen detectives have some or all of the following characteristics. I am a sucker for redemption tales, so I’m drawn toward wounded, tortured souls who are often edgy and unafraid of violence. I like non-conformists whose quirkiness makes them endearing and who frequently frustrate the more straight-laced “suits” around them. I favor characters who are driven, often by their own demons, to pursue a case that others might give up on and who have that inherent knack of knowing when an investigation is going in the wrong direction and who will doggedly pursue their instincts even when no one else may believe in them.

So, in reverse order we have:

5. Stephen Holder (The Killing)

For me and the three other fans who got hooked on AMC’s The Killing, the character Stephen Holder is worth every excruciating minute of some of the flawed elements of the show.

There are times where this show becomes maddeningly distracted by it’s multiple story lines and psychodramas, but the story is anchored by Holder (played by Joel Kinnaman) and his partner Sarah Linden (Mireille Enos) and their developing relationship. Holder is a recovering drug addict, a tall gangly white guy who talks, at times, as if he thinks he is black. However, his street sensibility and ability to relate to everyday people shows a sensitivity, and at times vulnerability, that is almost entirely absent in his partner’s character. In season 3 he gains entrance to the hangout of a hellish street gang by knowing their slang and despite their taunts, calmly approaches and dominates the gang’s hysterical pet pit bull, giving him a chance to try to glean some information from the thugs.

What makes Holder most endearing are his goofy one-liners and his use of language and metaphor. He tells Sarah in one scene, “Think of me as your sensei in the bloodsport of life.” Even in the context of the scene, I’m not sure what that means. Near the end of a scene in a hospital ward, an old man in a ratty robe pushing his way down the dingy hallway in a wheel chair, oxygen tank and all, approaches Holder who greets him with, “Yo, ancient player, got a smoke?” To the delight of the viewer, the old man pulls out a pack and offers it to Holder. “Don’t mind if I do, thank you sir,” Holder says as he extracts one from the pack. The old man rolls on down the hallway.

Holder also shows off flashes of insight as he stares at the board full of pictures of missing girls, victims of season 3’s serial killer. He suddenly realizes that he and Linden are getting nowhere studying victimology, but should be trying to get into the head of the killer. He blurts out to Linden, “See we been goin’ all Copernicus on this bitch (the case), when we should be Galileo; you feel me? He gets nothing but a skeptical stare from Linden (“What’s wrong with your face, Linden. Don’t stroke out on me.”), but explains that they need to become more like Galileo, adopt a more global perspective. “It’s not about what these girls see; It’s about what he (the killer) sees.”

You won’t see Holder chasing down a bad guy, or flashing a gun, or engaging in a car chase on a weekly basis. He’s a cerebral guy whose scars, humanity, and ability to turn a phrase push him into my top 5. Word is that AMC has dropped The Killing, but that Netflix has picked it up and will produce a season 4.

4. Detective John Munch (Law and Order SVU)

Watching re-runs of SVU remains a guilty pleasure for me especially when I come across an older episode that somehow slipped past me. However, even when I reach the point in an episode where I remember clearly what the outcome will be, I still enjoy the twists and turns and the fine ensemble cast.

I have to admit, though, that I dropped out of watching new episodes a few seasons ago. The show lost too many critical characters, particularly Stabler (Christopher Meloni), and the cases got creepier. So in reading up on Munch, it was news to me that he had “retired” and left the show. I think I can hear the sucking sound of a very good series going down the drain.

Richard Belzer’s Munch, is a grouchy, cynical detective who entertains the rest of the department with his rants against authority and bureaucracy and his encyclopedic knowledge of conspiracy theories. He created the character originally for the show Homicide: Life on the Streets (set in Baltimore) in 1993 and then made his way over to SVU as the same character in 1999. According to Wikipedia, “Munch has become the only fictional character, played by a single actor, to appear on 10 different television shows” including shows as disparate as 30 Rock, Arrested Development, and The X-Files.

Like Holder (The Killing), Munch provides contrast with his partners in part because of his crusty personality, but also because he is an intellectual who will frequently reference philosophy, history, literature and art, mostly to the quizzical stares of his partners or antagonists. In one episode, faced by a government official who refuses to give him information related to an investigation, patiently explaining repeatedly that what Munch wants is “classified”, Munch finally yells at him, “What are the odds you have a picture of Joseph McCarthy tattooed to your ass!”

Munch has the world-weariness that I see in a lot of detective characters, but it’s not just that he has seen too much, but rather that he has a Sisyphus-like nature; while his efforts will never stem the tide of crime and abuse, he has to try. He knows he is uniquely suited to the task so he continues to try to succeed in a broken system, working to solve the case in front of him, knowing that the cases will never end. One senses an abiding sadness in him although we know little about his background. Sometimes the sadness flares into fury as it does in a famous scene where he rails against a judge that he views as being too soft on a man they have arrested, gets slapped with a hefty fine, gets declared that he is in contempt of the court, assures the judge that he does have contempt for his court, and ends up in jail.

Well, Detective Munch, I’m sorry to hear you have retired. I will miss you. You certainly have earned a spot in the Law and Order Hall of Fame. Maybe you’ll finally have time to nail down just who it was on the grassy knoll in Dallas in 1963.

#3 Rust Cohle (True Detective)

I was pretty much hooked by this series from the moment I saw the opening montage of dark and moody images backed by the dusty, mournful lyrics of the Handsome Family’s song “Far From Any Road.” The setting is in Louisiana in 2012 but the fractured timeline challenges the viewer to constantly pay attention to where the storyteller is in the narrative which stretches back to the original, haunting case in 1995 and even further back into Cohle’s (played brilliantly by Matthew McConaughey) tragic past.

Cohle just happens to fit every criterion I set out in the beginning. He is tortured by the memory of a marriage and a child that he has lost and then by his descent into a long stint as a deep undercover agent, an experience that eventually lands him in a mental hospital wracked by drug abuse, PTSD, and insomnia. He rebuilds his life as a homicide detective teamed with Marty Hart (Woody Harrelson).

McConaughey’s dual portrayal of Cohle, as both the tightly wound 1995 detective that his colleagues call “The Taxman” because he carries about a ledger in which he keeps copious case notes, and as the 2012 chain-smoking apparent burn-out case, is truly remarkable.

As the narrative bounces between his initial investigation of a gruesome, ritualistic murder of a young prostitute in 1995 to an interrogation regarding that investigation being done by two newly assigned detectives in 2012, his deep cynicism, misanthropy, and fatalism remain consistent. Repeatedly, both his captain and his partner beg him to stop spewing out his nihilistic viewpoint, especially in front of other detectives and their superiors. During one point in the interrogation, when he reflects on the death of his daughter, he almost smiles, telling the detectives that he is happy that she did not suffer, and happy that she did not have to live in the world that he views as a morass of cruelty and evil.

The younger Cohle is comfortable chatting with a prostitute who not only gives him some vital information but also trusts him enough to sell him the Quaaludes, which he needs for sleep. When she appears ready to seduce him for free, he seems entirely detached and uninterested, driven on, it seems, more by the investigation than by any kind of moral code. Sex, at that moment, would just have been a distraction, a waste of time that he needs for the case. Likewise, he has no qualms about suddenly and viciously attacking two locals who he feels are withholding information from him that he needs. He extracts it quickly from them, returns to the car, slips on his jacket and continues on.

The older Cohle convinces the two new detectives that he is just a guy, living behind a bar who is willing to come in for a chat about an old case of his (the 1995 murder of Dora Lange), an interrogation that becomes an extended game of chess. He pulls out a cigarette and when told he cannot smoke gives them the choice. He gets to smoke, or he leaves. When the conversation reaches mid-day, he informs them that, “It’s Thursday and it’s past noon. Thursday is one of my days off. My days off I start drinking around noon. You don’t get to interrupt that” and sends them off to bring him a supply of beer that will get him through the afternoon.

The chess game is not just the perks that he is able to extort as he takes them through the case but Cohle’s efforts to determine the renewed interest in a case that had supposedly been solved long ago. He quickly deduces that they believe the true killer is still out there, something he has believed all along, something that eventually he must convince his old partner, Marty, to help him finally finish.

When Marty and Cohle are finally reunited, years seem to drop away from Rust as he reveals that he has never truly given up on the case, that he knew all along that they had never truly stopped the killer. He infects his partner with their former passion for justice, something that has been smothered by the corruption of Louisiana politics in this case.

After the creepy and dramatic resolution, when justice is finally served, Cohle, for the first time expresses a bit of hope for the universe in a final conversation with Marty. As they are walking away from the scene of the final showdown in the dark, they both look to the stars. As they compare light and dark to good and evil, Marty concludes that the darkness must be ascendant. Cohle, for once, sees it differently: “Once there was only dark. If you ask me, the light’s winning.”

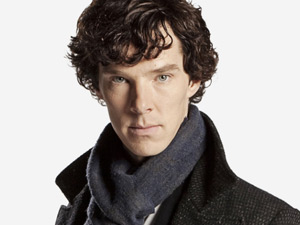

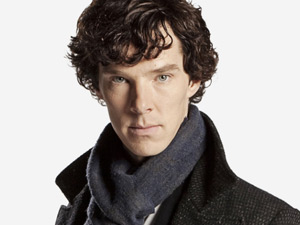

#2 Sherlock Holmes (Sherlock)

How could anyone not like this show?

Certainly, Sherlock Holmes (played by Benedict Cumberpatch) whips through some of his monologues in lightening style that defies my Americanized ears to catch every word, but the show’s clever use of graphics, and the knowledge that I don’t need to catch every word as Holmes verbally dissects a scene or an individual leads me now to shrug my shoulders,not unlike Watson and Lestrade, who simply stand by while Holmes is “at it again.”

Holmes is not the tortured soul seeking redemption as many other detective characters; in fact he is maddeningly self-absorbed. He is, however exceedingly high on the quirkiness scale and driven completely by any case that he does not find “boring.”

The producers have taken an iconic character and brought him into the 21st century unharmed. They have made dramatic changes from the characters created by Arthur Conan Doyle, and it seems that every one of them works. Watson (Martin Freeman) is not a blustering and often clueless accomplice, but rather a tested war veteran, anxious to be a part of the hunt. Lestrade (Rupert Grave), generally portrayed by Doyle as a bumbling antagonist, is instead Holmes’s defender and ally. Mrs. Hudson (Una Stubbs) provides both wise support and comic relief as she gently chides her unruly renter about shooting his gun into the walls to allay his boredom and helps to keep alive the running joke that Watson is gay.

Holmes himself remains quite intact. While they have softened Doyle’s character’s cocaine addiction into an overuse of nicotine patches presumably to quit smoking, Cumberpatch’s Holmes is still brilliantly observant, oblivious to many social niceties, and at turns both insufferably insensitive and surprisingly charming and thoughtful. That thoughtful side is always a surprise, but it comes through repeatedly with his fondness for Watson, his protectiveness of Mrs. Hudson, and his (eventual) tenderness toward Molly Cooper (Louise Brealey). The writers had planned for Cooper to be in only one episode, but viewers responded so positively to her character and her hopeless crush on Holmes that they continued writing her into subsequent episodes.

The writers have even studied Doyle’s stories and culled key elements while being unafraid to change them dramatically and artfully weave in the modern use of cell phones, texting, and computer hacking. Doyle’s A Scandal in Bohemia becomes A Scandal in Belgravia, but some key elements of the original–the introduction of Irene Adler, the royal family, scandalous documents—remain, as the 21st century challenges Sherlock to find the pictures locked in a cell phone, investigate “the woman” through a website that portrays her as a dominatrix, and eventually to swoop in and save her in response to her timely, almost final, text.

One particular element that separates Holmes from other TV detectives is that he is only interested in solving crimes for the intellectual stimulation and to fight off boredom and the depression that comes with it. He feels little or no sense that he is he is serving justice and doing a service to society. He feels no moral imperative to right wrongs. In fact, in A Study in Pink, he becomes giddy as evidence mounts that London is being plagued by serial suicides. He celebrates when visited by Lestrade in his role as “consulting detective” and wait for Lestrade’s departure before leaping into the air at the joy of the coming challenge: “Brilliant! Yes!! Ah! Four serial suicides and now a note! Ah, it’s Christmas!” Mrs. Hudson tries to rein in his enthusiasm to no avail: “Look at you, all happy: it’s not decent.” Sherlock replies, “Who cares about decent. The game, Mrs. Hudson, is on!

In re-watching Cumberpatch at work, I’m not sure there is another actor alive who could pull off the character they have created for this wonderful series. He is positively brilliant with his deadpan humor and pitch-perfect comic timing.

As a long-time fan of Sherlock Holmes, it is great to have him back, more clever, more complex, and more fun than ever.

#1 DCI John Luther (Luther)

Detective Chief Inspector John Luther (Idris Elba) does not walk. He stalks and swaggers his way though the grim streets of London often with his hands jammed into his pockets, moving from crime scenes, to interrogations with criminals, to prison cells, to the police headquarters often cloaked in grey shirt or grey overcoat.

In truth, Luther lives in a grey world. The cinematography seems to continually project these dingy tones, and I suspect if London ever were to have a sunny day, that filming of the show would be cancelled.

It is established early on that Luther is a man driven by absolute conviction and plagued by moral ambiguity. In the first scene of the first episode, he allows a truly heinous pedophile to dangle from a beam inside a warehouse until he gives up the location of a kidnapped child. Instead of rescuing him immediately, Luther, clearly in anguish, questions him about the other children he has tortured and killed and tries to extract even more information, until the man (Henry Madsen) finally can hold on no longer and plunges to the floor, critically injured.

Even though Luther is cleared of any wrongdoing, the next episode finds him on the roof of the police station standing at the very edge and contemplating the street far below. A fellow detective finds him and begins to talk him down, reassuring him that no one would shed a tear over the injuries to Madsen. Luther responds, “Doesn’t make it right” to which his colleague replies, “It does make it a little less wrong.”

And this is Luther’s world. He is surrounded by unsavory criminals with whom he must work, and sometimes negotiate, in order to solve a case or protect a loved one. In one of the most bizarre and chilling twists, he finds himself initially threatened by the psychopathic Alice Morgan (Ruth Wilson) who eventually turns into a trusted ally. She has committed a double murder that he cannot prove her guilty of and over time comes to think of herself as John’s protector.

Because he is unafraid to work outside the law and occasionally to defy authority in his search for justice, he is, like some superheroes (Batman and Spiderman come to mind) thought to possibly be criminal himself. Up on the rooftop, he even questions his own actions as he talks with his colleague asking, “Do you not worry you’re on the devil’s side without even knowing it?” As time goes on he comes under the active scrutiny of a female investigator, DS (Detective Sergeant) Gray (Nikki Amula-Bird) who actively suspects him of wrongdoing. She turns to Luther’s loyal protégé DS Justin Ripley (Warren Brown) to confide in him and share her suspicions and observations that Luther is a “dirty” cop. Ripley tries to explain to her that, “there’s a difference between getting your hands dirty, and being dirty.” (Note: all of the quotations sound much cooler with a British accent.)

As he stalks though the world, Luther appears alternately weary, disgusted by the humans he must deal with, and confident that somehow he can make a difference. He confides at one point that, “I’ve been a police officer since God was a boy.” When in one scene, Alice confronts Luther’s estranged wife, Zoe, and asks why John pursues his work when it has cost him so much including his wife. Zoe answers evenly, “He believes that one life is all we have, life and love. Whoever takes life, steals everything.” In defending the lives of others, he seems to care little about his own; he lives not expecting love or hope. In a conversation with one soul whom he has saved, she tells him, “You should be married, be happy and everything.” He quietly replies, “No one will have me.”

Zoe’s assessment of him gives us the clue to his obsessive dedication to the work. He never seems to sleep and never pursues a relationship once he has lost his wife. In a crime scene, he has Sherlock-like instincts, observing the evidence of a double homicide, analyzing the probable sequence of events, and then confronting his partner, Ripley. “Am I missing something? Does that seem right to you?” Ripley replies, “None of it seems right to me.” Luther then states, “’Cause it’s not right, is it? It’s not right.” Luther is not someone who breezes in with all the answers, but as the team struggles to put the pieces together, he repeatedly uses variations of the phrases above: “What am I missing?” “Something is missing.” “This isn’t right. “ However, the questions frequently bring on the insights he needs, and he bolts off on his own, confident that he has found the key to unlock the case.

Viewers will either find Luther as a man looking to die or a man so confident in his way of doing things that he has a kind of bravery that borders on the foolhardy. In the jaw-dropping finale of series 2, a case where the team must track down and stop a pair of psychopathic twins playing a game of murder and mayhem, Luther offers himself up as a sacrifice. As he approaches one of the twins, unarmed, facing off against the young man who is holding a “deadman” switch connected to a suicide vest with enough explosives to destroy a city block, Luther soaks himself in gasoline, tosses the man a lighter, and encourages him to roll the dice with which he and his brother have been creating havoc. Either the man will give up, or he gets to immolate Luther. Luther’s ploy ends up being a brilliant move in a chess game where he ends up being just one move ahead of the suspect.

Luther ends up being my #1 because of the magnificent work of Idris Elba. With many of the other characters, I marveled at the skill of the actors. I never felt Elba was acting. He becomes Luther. According to my reading on this show, it was never meant to be more than one series. However, plans are in the works for a full-length feature film.

Conclusion

Whew! This was a lot of work!! I’ve gotten so many great comments and suggestions, and I know that I could do this all over again and come up with 5 other great detective characters. Someone should absolutely do the 5 best female detectives, just to balance out my lack of gender equity. Maybe I will take that on later, but this has been so consuming that I have not fed my wild birds in the back yard for 3 days and have barely looked at my vegetable garden. The massive up-side is that I have been able to re-watch hours of these great shows in the name of research. Labor of love!